Life may be returning to some kind of new normal. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has greatly impacted our collective mental health and Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) services themselves. Through these trying times we have seen how external factors have impacted psychological therapy services and patient outcomes. This has highlighted the need to consider, in more detail, how geography, weather, socioeconomic status and other external factors are likely to affect our mental wellbeing.

Research into the links between neighbourhood factors and psychological health is not new and has been carried out throughout the 20th and 21st centuries [1]. Previous studies have shown associations between outcomes related to common mental health disorders and a range of external factors. These include population density [2,3], employment status [4,5], working hours [6], local crime rates [7], and deprivation [8,9], to name but a few.

UK Census Data: socioeconomic factors on mental health

The UK census data is a vital resource in researching how external factors influence the mental health of different geographical areas. And, in turn, the impact these have on mental health care provision. Previous studies have tended to focus either on the population or the individual, with very few focusing on finding the joint effect of both population and individual characteristics on mental health outcomes [10].

A key takeaway from the recent MQ Mental Health Science Summit stated “We need to focus on solutions, not only document our decay”. This means that mental health science should connect with needs, demands and constraints in real life. Being able to quantify the extent of the impact of socioeconomic factors on mental health outcomes could help IAPT service providers when monitoring performance. Not to mention ensuring the right solutions are used in the right areas.

Combining socioeconomic metrics to report on mental health

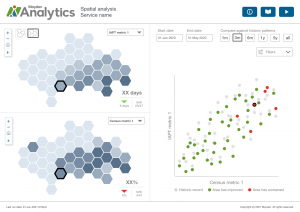

Here at Mayden, we have been developing spatial analysis tools which combine socioeconomic metrics from the UK census, such as economic activity and working hours. These metrics are closely associated with IAPT service provider performance indicators such as patient DNA rates, the number of referrals and recovery rates. This builds on previous research we have undertaken to understand the needs of the IAPT community.

We are developing a new dashboard for this analysis in iaptus. The dashboard will enable IAPT providers to combine session level treatment outcome data and patient characteristics with socioeconomic census metrics. To the left we see a prototype dashboard displaying the association between possible census and IAPT metrics.

This dashboard will enable IAPT service providers to:

- Compare different geographical areas to investigate differences in referral rates, drop-out rates, recovery rates by socioeconomic status or other census metrics.

- Visualise patient demographics geographically, such as gender, age, employment and patient response to treatment.

- Visualise therapist caseloads geographically.

- Highlight areas in need of outreach or targeted advertising which are performing below the expected outcome thresholds.

Want to learn more? We’d Love to hear from you

We’re looking forward to releasing this new dashboard soon. We will also be able to offer IAPT service providers with the support of our expert analytics team to make the most of these new kinds of visualisations and insights from their service data.

We’d love to hear from NHS and private mental health providers of IAPT services who are interested in hearing more about this workbook and the associated analysis.

We’re grateful to the IAPT services that have already expressed interest in this project.

If you would like to join them or find out more about the impact of socioeconomic factors on mental health, please contact us at projects@mayden.co.uk.

REFERENCES:

[1] Faris, R.E.L. and Dunham, H.W., 1939. Mental disorders in urban areas: an ecological study of schizophrenia and other psychoses

[2] Gruebner, O., Rapp, M.A., Adli, M., Kluge, U., Galea, S. and Heinz, A., 2017. Cities and mental health. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 114(8), p.121.

[3] Cain, D.N., Mirzayi, C., Rendina, H.J., Ventuneac, A., Grov, C. and Parsons, J.T., 2017. Mediating effects of social support and internalized homonegativity on the association between population density and mental health among gay and bisexual men. LGBT health, 4(5), pp.352-359.

[4] McManus, S., Bebbington, P.E., Jenkins, R. and Brugha, T., 2016. Mental health and wellbeing in england: The adult psychiatric morbidity survey 2014. NHS digital.

[5] Van der Lem, R., Stamsnieder, P.M., Van der Wee, N.J.A., Van Veen, T. and Zitman, F.G., 2013. Influence of sociodemographic and socioeconomic features on treatment outcome in RCTs versus daily psychiatric practice. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 48(6), pp.975-984.

[6] Afonso, P., Fonseca, M. and Pires, J.F., 2017. Impact of working hours on sleep and mental health. Occupational Medicine, 67(5), pp.377-382.

[7] Dustmann, C. and Fasani, F., 2016. The effect of local area crime on mental health. The Economic Journal, 126(593), pp.978-1017.

[8] Delgadillo, J., Asaria, M., Ali, S. and Gilbody, S., 2016. On poverty, politics and psychology: the socioeconomic gradient of mental healthcare utilisation and outcomes. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 209(5), pp.429-430.

[9] Saxon, D., Fitzgerald, G., Houghton, S., Lemme, F., Saul, C., Warden, S. and Ricketts, T., 2007. Psychotherapy provision, socioeconomic deprivation, and the inverse care law. Psychotherapy Research, 17(5), pp.515-521.

[10] Propper, C., Jones, K., Bolster, A., Burgess, S., Johnston, R. and Sarker, R., 2005. Local neighbourhood and mental health: evidence from the UK. Social science & medicine, 61(10), pp.2065-2083.